Sensory Trauma and Proactive Regulation

By Emma Reardon

Dealing With Our Sensory Experiences

“But it hurts!”

“Don’t be silly, it doesn’t hurt. Stop making a fuss”

Like many people whose sensory experiences are different to those of their peers, I heard endless variations on this verbal exchange whilst growing up – and into adulthood too.

Was I somehow more sensitive? Was I less resilient? Or was I simply attention seeking, deliberately awkward and making a fuss? The answer is I was none of these.

Each of us experiences the world through our senses; all those sensations that come into our body from our environment (touch, taste, smell, sight, hearing), plus those that arise within our body (proprioception, vestibular, interoception). These last three sense systems are less familiar to some people and provide information about where our body is and what it is doing (proprioception); the effects of gravity and movement on our body (vestibular); and detecting and labelling internal sensations like emotions, pain, feeling tired or hungry (interoception).

Every single one of us has sensations we prefer, sensations we seek out and those we avoid. We each need different amounts of sensation to feel balanced and able to take part in the world around us. Autistic people tend to experience sensory information differently. To go back to my opening questions, it’s not about coping, resilience or being awkward. Autistic people frequently experience sensory information in muted or heightened ways compared to non-autistic people. This means that our brain may perceive too much or too little sensory input for us to be able to take part in things or to feel safe in our surroundings.

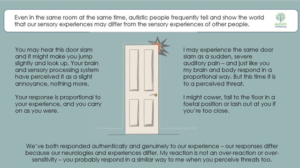

What can make things tricky is the fact that the people we share our surroundings with may be unaware of how differently our sense systems work. I’ll share an example my colleague Rorie and I use in our training and talks.

Differing Sensory Experiences

Imagine you have two people in a room together. An Autistic person – that’s me! And a non-autistic person; Rorie. Suddenly the door slams shut with a loud bang. In this imaginary scenario, the noise makes Rorie jump, and it distracts him from what he was doing for a moment, and he feels a little annoyed. On a day where he was feeling particularly stressed out by his workload or life events, he might even be a bit snappy at whoever had let the door slam. But on this occasion, he notices his annoyance, shrugs it off fairly easily and gets back to work. All a totally proportional response to a slamming door.

I, on the other hand, as someone who experiences sudden, unexpected noise as auditory pain, have a very different response. The noise of the slamming door sears through my head and physically hurts. I flinch and cower. If I was having a bad day, I might even lash out at someone nearby or curl up in a fetal position on the floor. But on this occasion, I feel intense pain, very frightened, and unable to get back to my work. I too have responded in a proportional manner to the sound of the door slamming.

My reaction is different to Rorie’s because my sensory experience is different. I haven’t over-reacted, my brain and body have automatically responded to the threat I perceived. If Rorie’s brain was to perceive a threat of equal intensity – for example, a loud firework being let off in the room next to his head – he would respond instinctively, like me, with a survival response of fight, flight, or freeze.

Sensory Trauma

Autism Wellbeing CIC have written a position paper called Sensory Trauma: Autism, sensory difference and the daily experience of fear. Many Autistic people have told us that our paper accurately described and also validated their experience. Indeed, through our vocalizations, gestures, words, blogs and vlogs, Autistic people have, for a long time, been telling and showing the world that our sensory experiences are different.

We use the term Sensory Trauma because it is experienced in a person’s body like other types of trauma. The imaginary scenario of the slamming door is an example of this. An Autistic person’s brain may perceive a physical threat from sensory input that activates a survival response in their body and this can result in fight or flight behaviors like shouting, hitting, or running away, or freeze responses like collapse, disconnection and being unable to move. Events and interactions that might give rise to Sensory Trauma may not be the types of events or interactions we would typically consider traumatic, such as war, disaster or being assaulted. The concept of trauma has a quality of doubleness. SAMHSA gives the following definition: Individual trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being. This means that one person may find something traumatic, that another person doesn’t.

An Autistic person experiencing Sensory Trauma may have survival responses to perceived threat throughout the day and in relation to sensory information in the environment that other people in the same environment may not even be aware of. This can make the environments that autistic people spend their time in feel unpredictable, unreliable, and unsafe.

Proactive Regulation

Avoiding Sensory Trauma feels like a full-time job! With my sensory processing system requiring such different amounts of sensory input, compared to the non-Autistic majority of people, I am at risk of experiencing Sensory Trauma frequently over the course of my day. The one thing I know for sure is that something will happen on a sensory level that will be painful or distressing to cope with, but I am never quite sure when, or what form it will take. Will it be the smell of perfume when I visit that client? Will there be a fire alarm practice when I go into the store? Maybe the fluorescent lights in the office will be flickering?

Of course, it’s not possible for me to avoid sensory input that I experience as distressing or painful. I do my best to keep myself balanced by practicing ‘Proactive Regulation’. As the name suggests, this refers to regulating my senses proactively. For me, Proactive Regulation is about giving yourself, or the person you support a good dollop of positive sensory input before an event or interaction that may or is likely to prove dysregulating. It also includes going equipped with sensory resources that may regulate me in the moment or provide regulation simply by their presence in my pocket.

Going equipped means I take my noise cancelling ear-buds, or failing that I always have a set of ear plugs in their carry case keyring on my keys. I have a nasal inhaler tube that I have made with essential oils that I find grounding and can cut through the aftereffects of diesel fumes, the takeaway burger van, or perfume. I keep objects in my pocket that give me lots of sensation in my hands, a pinecone or a favorite smooth stone. Sensory regulation is not just about blocking out or reducing those sensations that I experience in a heightened way, its about increasing input where I experience muted sensations. It’s all about balance. The proactive part of this regulation is important because I have learned through experience that it is easier to remain ok than to try to become ok after I have become dysregulated.

Proactive Regulation isn’t a cure-all. It will never compensate for a sudden unexpected noise, or other intense sensory experience. What it does do, however, is put me in a more balanced starting place. Instead of spending my days dysregulated where any sensory event might be the final straw, I am more balanced and able to process sensory input so that I can carry on about my business.

Of course, other people can help with regulation too, via the process of co-regulation. I will write another blog about this and our follow up work to Sensory Trauma: Autism, sensory difference and the daily experience of fear.

Emma Reardon is one of the directors of Autism Wellbeing CIC, a non-profit organisation working alongside people to change the way autism is perceived. Emma’s professional career spans almost 30 years within the field of social care. Emma has been published in the BILD Good Autism Practice Journal and is one of the co-authors of Autism Wellbeing’s ground-breaking work, “Sensory Trauma: autism, sensory difference and the daily experience of fear”. Emma also blogs about being autistic in Undercover Autism – an insider’s experience and she shares her lifelong passion for the natural world in her blog Off Down The Rabbit Hole.